Research project of MA students in the Museums in Context course at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, MA Cultural Economics led by professor Trilce Navarrete.

Authors: Xue Mi, Ziyou Bao, Nicolò Morando

All images courtesy of the authors.

Let’s begin with some numbers

Rotterdam is the second-largest city in the Netherlands after Amsterdam and is a major logistics and economic centre in Europe. Its extensive distribution system including railways, roads and waterways has earned it the nickname “Gateway to Europe and the World”. Rotterdam hosts Europe’s largest seaport, which is the sixth biggest in the world. As of January 2020, the city had 651,446 inhabitants and encompassed over 180 nationalities that form a diverse, multi-ethnic population and student force. Rotterdam is the most multi-ethnic and multicultural city in the Netherlands, with demographics differing by neighbourhood. Ahmed Aboutaleb, mayor of Rotterdam since 2009, is of Moroccan descent, which fits the high multiculturalism of the city: almost half of the city’s population is of non-Dutch origin. In this study, we take into consideration the international students population of Erasmus University, which has continued to increase reaching almost 7000 students in 2020.

From the previous data, we can see therefore that the population of the city holds an extremely rich cultural diversity, composed of Dutch people living together with various second generations of migrant descent from different backgrounds (e.g. Indonesian, Chinese, Capo Verdians, Marocchians, Turkish). Because of these characteristics, Rotterdam is included with other large cities in what can be called the category of “super-diverse cities”. Language represents a fundamental aspect of this diversity, defining the identity of communities together with other intangible practices. such as oral expressions, celebrations, songs and rituals. Mother languages in fact are protected by UNESCO, for constituting an essential part of an ethnic community as a carrier of values and knowledge.

Along with being a source of enjoyment and wonder, museums represent also an important educational asset for the people of Rotterdam, as in their definition they are called to “acquire, conserve, research, communicate and exhibit the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity” (ICOM, 2007). Museums that provide multilingual services, therefore, can contribute not only to the preservation of fundamental intangible aspects of cultures but also, as in the case of Rotterdam, a more comprehensible instrument of education for international students.

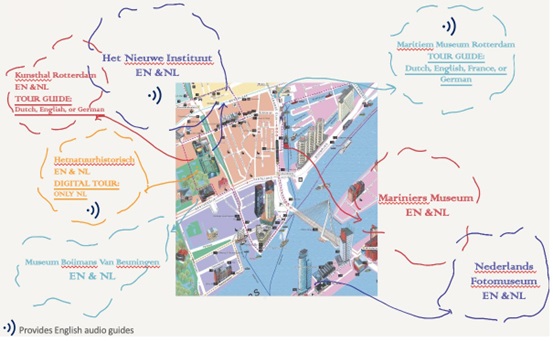

Museums service in Rotterdam. Made by ziyou.

Our research aims to investigate how diverse language services may influence international students’ museum experience in Rotterdam. We collected data of the 7 mostly visited museums in Rotterdam about their multilingual services provided and conducted a qualitative survey on Erasmus international students. What follows is the summary of the 47 respondents (13 male, 34 female, across a wide range of age and different educational background) from 14 different linguistic background who answered our questionnaire.

Perception on museum language services in improving learning and visiting

Our results suggest that textual tools such as ‘Labels of collections’ and ‘Pamphlets’ are the most popular language services among respondents. In terms of learning, ‘Labels of collections’ and ‘Personal tour guide’ are valued as the most effective language tools. Our respondents rated the specific tools being provided in their first language, a dominant percentage (‘pamphlets’ 81.25%, ‘QR codes/digital pamphlets’ 75%, ‘audio guide’ 81.25%) was answered by the respondents, showing their agreement on the importance in their learning experience. In terms of which aspects museum multilingual services may improve the most, 47.92% of the respondents recognize its significance to ‘visitors’ experience’ and 22.92% reckon the importance to ‘equal access to information’.

Other key points and implications:

Insufficient language services: firstly, audio guides were used by half of the respondents (46%) while 4% reported ‘never’ using them. This is not surprising since during our field study, we found some museums in Rotterdam do not provide audio devices and instead provide QR codes for consumers to use their own devices to access additional information.

Lack of language choices: insufficient language services is the first issue being identified. Apart from noting the lack in devices, respondents identified the second issue being the lack of language choices and wished for greater diversity by stating ‘more Spanish guides’, ‘I think French and Spanish explanations should be provided more’, ‘ignore the need for local immigrant communities, Like the Turkish immigrants in Rotterdam’, ‘only Dutch and English’, ‘at least make the labels available in English, rather than just Dutch’.

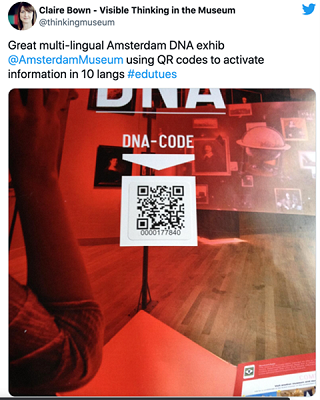

the post of a visitor who experienced the multilingual guide services in the Amsterdam Museum

“With this QR code you can scan your leaflet, the film will start in your language. This is the technique we’re using to reach out to the international audience, which we so far find very successful. It’s more welcoming and you make it easier for people to look and explore. That’s what you really want people to do in the museum – to look.” (Ward, 2019)

In strike contrast to the Rotterdam museums, the Amsterdam museum recorded short films and voiceovers in 10 different languages to make the museum more accessible to international visitors. The audio guide pick-up rate is now 67%, with 60% of the visitors listening to at least half of the stops! (GUIDE.ID)

Then, how can museums promote their language services ?

Our respondents provided several ideas and believe museums could involve communities, so as to co-develop multilingual services to be made available online (social media platforms, podcast etc.).

Recently, podcasting has become very popular among global art lovers, museums, researchers, the professional audiences who would like to share stories of exploration, innovation, and discovery about the latest exhibitions. There are many forms of museum-related podcasts, let see what frontrunner do:

(1) The podcast Queer History Talk is hosted by the Amsterdam museum itself and updated periodically, it talks about current exhibitions and projects with various guests, interspersed with performances by artists from different disciplines. It also invites English speakers.

the screenshot of the podcast Queer History Talk

(2) The Musée d’Orsay has launched its ‘Promenades Imaginaires’ podcasts, which release one season at a time. The author Béatrice Fontanel chose these paintings in the museum to imagine the stories visitors will hear.

the screenshot of the podcast The Musée d’Orsay

(3) MUSEELOGUE is a Chinese podcast about museums hosted by museum practitioner Yu and her friends. They collaborate with museums to provide the latest exhibition information, experiences, and stories behind exhibitions.

the screenshot of the podcast MUSEELOGUE

Translation quality needs to be improved:

The third issue identified is that some translations of museum language tools, either it be English or other languages, are far from accurate, ‘the translation needs to be more creative and fit in the English context’, as one respondent stated. To improve the correctness, the following example may shed some light on this project.

“Baggage Storage” is more often used in the airport instead of “Left Luggage”

Before the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, the city has decided the time is ripe to do away with the old signs that were run through a first-generation machine translator in order to produce the English copy. The translation is carelessly made without English context consideration. How did the local government improve that? – Encourage the individual’s enthusiasm: each social media user can upload the wrong translation of the signs and add revised suggestions to the government’s official account.

In summary, our project reveals a great lack of language services and linguistic diversity in Rotterdam museums. The examples provided of alternative linguistic solutions showcases the benefit on individual learning experience if more languages and better-quality devices are provided, along with community activities and strategic collaborations are considered. Future research may look into the effect of diverse language practices in museum context worldwide.

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.