Text by Caterina Sbrana.

I propose a very interesting history page that you can explore through the vision of 2,200 images available online in the Siberian Expedition Digital Archive.

Created by Canadian historian Benjamin Isitt and the University of Victoria Humanities Computing and Media Centre, the website about the Canada’s Siberian Expedition is based on a participatory approach, integrating learning resources, an online journal and Digital Archive. As explained in the web-pages of the Archive, the images come “from public archives, family collections and rare secondary sources” and they are “fully searchable in English, French, and Russian”. The Archive offers also participatory features, inviting people who “have photographs, letters, or a diary on Canada’s Siberian Expedition gathering dust” to contribute to the Archive with their materials, granting the permission “for non-profit educational usage of the images”.

In addition to offer to the users the opportunity of going through the images of the Archive, the website provides an interesting review of the historical context in which the expedition took place and the reason why 4,200 Canadians were sent to Vladivostok.

In 1917, Russia, engaged since three years in the First World War alongside the Triple Entente, had to face a series of internal problems that forced it to withdraw from the world conflict. The losses in terms of man and land, which occurred because of the world conflict, the tsarist absolutism and the worsening of the living conditions of the Russian proletariat and peasants were among the triggers of the October Revolution that brought to power the Council of People’s Commissars. From here, a bloody civil war begun, ending with the victory of the Red Army (Bolsheviks) on the White Army (counter-revolutionaries).

What was then the role of Canada after the fall of the last tsar Nicholas II? On siberianexpedition.ca we can read that: “According to machine-gun officer Raymond Massey, «The expedition was to complete what Winston Churchill had termed the ‘Cordon Sanitaire,’ which was to contain the Bolshevik revolution.»” It then continues: “This was the context in which Canada’s Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, committed troops for Russia. Borden spent the summer of 1918 in London, where the Imperial War Cabinet decided to intervene on four fronts surrounding the Bolshevik government. Because of Vladivostok’s geographic proximity from Canada’s West Coast, 1,500 British troops were placed under the Canadian command.”

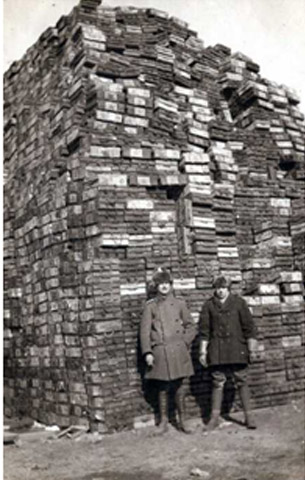

The following picture shows a surprising amount of ammunition stockpiled on the Vladivostok wharves, which were shipped by the Canadians to aid the tsar’s forces before the Revolution.

Percy Francis Collection, Las Vegas, Nevada

The story of Canada’s intervention continues: “Canada’s privy council approved the formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) as an array of foreign troops converged on Siberia and the Russian Far East: 70,000 Japanese, 12,000 Americans, 2,000 Italians, 12,000 Poles, 4,000 Serbs, 4,000 Romanians, 5,000 Chinese, and 1,850 French troops. When combined with the Czecho-Slovak Legion and White Russian forces, the total anti-Bolshevik strength between the Urals and the Pacific exceeded 350,000 troops.

In November 1918, the war ended on the Western Front and the White Russians underwent a change of command. Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak, former commander of the Czar’s Black Sea fleet, staged a coup at the Siberian city of Omsk. Kolchak proclaimed himself dictator of an “All-Russian government,” promising to unify White forces. The Allies had their point man in Siberia. “

Talking about life in Vladivostok in that period, siberianexpedition.ca tells that “The recollections and photographs of soldiers such as Eric Elkington offer rich insight into the social life of the military force and relations with Vladivostok’s civilian population, including a large number of ethnically Chinese and Korean residents and refugees from the Siberian interior. Soldiers’ recollections also reveal the dark side of military interventions – violence, human suffering, and the sex trade.”

The Siberian Expedition website and its Digital Archive are important resources to start learning about this controversial moment in the history of Canada and Russia, offering points for reflection and debate to world educators and students.

The Siberian Expedition website and its Digital Archive are important resources to start learning about this controversial moment in the history of Canada and Russia, offering points for reflection and debate to world educators and students.

Family photographic archives, increasingly digitized, are very important historical and iconographic resources for telling the story of a community, but also of an entire nation. These resources become even more relevant when they are combined with digitised public archives, and all the materials is openly accessible and usable by all researchers, as it is in the case of the Siberian Expedition Digital Archive.

Furthermore, digital photographic resources do not suffer from the decadence that the flow of time causes on the printed photographs, preserving a vast range of knowledge that can stimulate further study and research.

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.