Research project of MA students in the Museums in Context course at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, MA Cultural Economics led by professor Trilce Navarrete.

Authors: Tessa de Boer, Emmy Hermans, Julia Rokos

During the first lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic you could find digital museums on every corner of the internet, could this have been a prelude of a digital future for museums? Digital museums, accessible from anywhere in the world, are becoming more common. Many household names such as the Louvre, the Guggenheim, or the Uffizi Gallery are already offering vast online tools to make their collections more accessible and future-proof. The impact of world-wide lockdowns increased the demand for virtual experiences like those offered by digital museums (Tissen, 2021). However, it remains unclear whether this trend will carry on, leaving museums unsure of how to make sure their impact is built to last and how digital could benefit the physical museum.

Rijksmuseum Eregalerij video presentation

Rijksmuseum Eregalerij video presentation

Mauritshuis video presentation

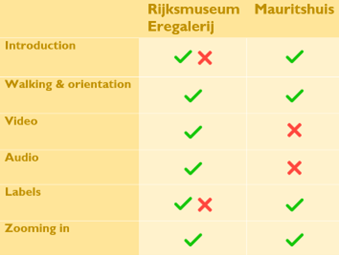

In order to understand how audiences of a traditionally physical museum interact with the digital counterpart thereof, we conducted a research consisting of a content analysis of two Dutch digital museums followed by a short survey to test our findings in a small audience. We chose two renowned Dutch museums that share their collection digitally, the Mauritshuis en the Eregalerij of the Rijksmuseum. The content analysis focused on, amongst others, user-friendliness, quality of the paintings and availability of additional information. The table below shows the presence or absence of certain aspects in both digital museums.

In short, both museums offer a virtual experience of their otherwise entirely physical collections. The Mauritshuis made its entire permanent collection available online, and the Rijksmuseum virtually opened up the Eregalerij, featuring some of the museum’s most prominent artworks.

In short, both museums offer a virtual experience of their otherwise entirely physical collections. The Mauritshuis made its entire permanent collection available online, and the Rijksmuseum virtually opened up the Eregalerij, featuring some of the museum’s most prominent artworks.

The digital museum of the Eregalerij starts with a small introduction video and welcome, however, no additional information about the museum or digital tool is given. The user can walk around using a mouse or buttons on the screen and an orientation map with all the artworks on it guides the user. The user can zoom in to some extent on both the artworks and the labels, although labels are not always readable. For some artworks, zooming in to a great extent is possible, as well as playing an informative video, wherein more is told about the artworks, and textual information, extends the museum label. Lastly, the digital museum offers a game for children.

The Mauritshuis digital museum starts at the first floor. Users start with an introductory video, giving a tour through the digital museum about the digital museum, the Mauritshuis itself and the collection guided by the Mauritshuis’ director. Walking around is possible by moving from room to room or by using the map. Zooming in and reading labels of each artwork is possible, however, only on some artworks, it is possible to zoom in to an even larger extent, allowing users to see the artwork in great detail. Aside from the labels, no additional information is available. Whereas the Rijksmuseum only shows the Eregalerij, digital visitors of the Mauritshuis can walk through the entire museum and enter any room they wish. An extra of the Mauritshuis digital museum is the option to view the museum in VR using Google Glasses.

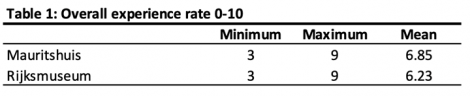

To follow up on the content analysis we conducted a small survey (Rijksmuseum N=12, Mauritshuis N=12) where respondents were asked to visit one of the digital museums and rate specific aspects of their online visit as well as their overall experience. First of all, the interesting part of this research was that we could see that a portion of the respondents would not complete the survey after being asked to visit one of the digital museums for approximately 5 minutes. Apart from other reasons to not fill out a survey for such a long period of time this could indicate that digital museums ask the visitor to put in effort which they are not always willing to.

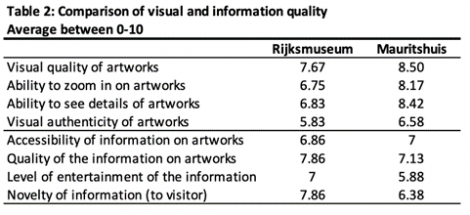

Respondents that were willing to visit a digital museum rated the visual qualities of the museums such as visual quality of the artworks and zooming-in options. As the content analysis shows, the Eregalerij of the Rijksmuseum offers a number of technological extras and options for the visitor such as audio, videos for certain artworks and a challenge for children. The results show that while an online exhibition is technologically enhanced like the Rijksmuseum, visitors do not necessarily rate this experience higher. Surprisingly, visitors gave an overall grade (0= worst, 10=best) of 6.85 for the Mauritshuis and a 6.23 for the Rijksmuseum.

The score indicates room for improvement for digital museums. Another question that was posed to respondents was whether or not they are now interested in visiting the physical museum. Interestingly, respondents of the Mauritshuis showed a higher interest in the physical museum, underlining the importance of a digital presence in attracting potential museum visitors. Additionally, digital Mauritshuis’ visitors were more interested in visiting a digital museum again.

Which aspects of a digital museum can be enhanced? The visual qualities of the Mauritshuis exhibition were overall rated higher than those of the Rijksmuseum, as seen in table 2, which could influence the higher overall experience. However, the information quality of the Rijksmuseum exhibition scored relatively higher than the Mauritshuis’. The content analysis also shows that the Rijksmuseum provides various types of additional information options and more information in general than the Mauritshuis. Possibly resulting from this; respondents rate the novelty of information in the Rijksmuseum with an average of 7.86 compared to Mauritshuis’ 6.38, although this does not result in a better rated overall experience. When considering the set up of the online exhibitions and the content analysis this could be credited due to the greater awareness of the Mauritshuis of where to start the exhibition. Falk and Dierking (2012) suggest that the museum visit does not only exist within the museum but the time leading up to and following the visit affects the overall experience of a museum. Mauritshuis seems to be aware of this by placing the visitor immediately on the first floor, in which the exhibition space is more visually appealing, donning bright colors and lighting.

The quantity of artworks or state of the art technological enhancements does not necessarily result in a high visitor’s satisfaction with a digital museum visit. As the Dutch report ‘Stand van het Nederlands Digitaal Erfgoed’ (Kemman et al., 2021) concludes, in 2021 digital heritage specialists and museums focus on the improvement of quality of the heritage that they exhibit such as providing information rather than the quantity (e.g. online databases), which can be seen in both museums as well. The Dutch ministry of OCW has set a goal of making heritage accessible to everyone by intensifying the supply of digital heritage and thereby focusing on visitor’s needs. Being aware of the visitor’s perception of a museum could increase visitor’s satisfaction as well as considering the before, during and after stages of a digital visit like the Mauritshuis. However, important to note is that a digital museum can never be the same as a physical museum and by implying it is, visitor’s will always compare it to the ‘real deal’. Museums could possibly increase their visitors’ experience by not focusing on imitating the physical museum, as seen in both Mauritshuis and the Rijksmuseum, but should aim to create a completely new digital experience, making it a heritage destination in itself (Li, et al., 2012). This way digital heritage tourists visit the museum merely online and not in relation to a potential or past physical visit (Navarrete, 2019). Future research could explore the possibilities and limitations of such a digital museum.

In conclusion, our analysis identified several key elements of the two digital museums, suggesting that there is a sort of ‘formula’ to developing such digital experiences. Most notably, many of the elements present in a physical museum were translated rather literally into the digital sphere. For example, the orientation maps, the audio guides, and museum labels. These are key elements expected at a physical museum, hence, they are also included online. Compared to the physical museum, both were exact digital models thereof, mimicking the physical visit as closely as possible.

Furthermore, the findings from the survey suggest that there are some specific elements visitors look for and expect from digital museums. First, we concluded that the preference for the Mauritshuis is related to its physical appeal, with bright and inviting colors and rooms as opposed to the gray and muted rooms of the Rijksmuseum. Additionally, features such as zooming in and additional information (text, videos, audio) were appreciated, however not all respondents made use of these. We also saw that visitors who enjoyed the digital tour were willing to visit the physical museum after. Although physical and digital museum experiences cannot be the same and valued similarly, digital museums could serve as a “preview” in addition to physical museums, allowing visitors to experience the museum before deciding to physically visit.

Bibliography

- Falk, J., & Dierking, L. (2012). The museum experience revisited. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Li, Y., Liew, A., & Su, W. (2012). The Digital Museum: Challenges and Solutions. Encyclopedia of Information Sciences and Technology. 4929-2937. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-5888-2.ch486

- Navarrete, T. (2019). Digital heritage tourism: innovations in museums. World Leisure Journal, 61(3), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2019.1639920

- Kemman, M., Hanswijk, M., Grond, A., Weemhoff, J., Bongers, F., & Van der Graaf, M. (2021). Stand van zaken van het Nederlands digitaal erfgoed 2021. Rapport | Rijksoverheid.nl. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2021/12/22/stand-van-zaken-van-het-nederlands-digitaal-erfgoed-2021

- Tissen, L. N. M. (2021). Culture, corona, crisis: best practices and the future of Dutch museums. Journal Of Conservation And Museum Studies, 19(1), 1-8. doi:10.5334/jcms.207

These days, from 4 to 6 May 2022,

These days, from 4 to 6 May 2022,

More information at:

More information at:

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.

If you have interesting news and events to point out in the field of digital cultural heritage, we are waiting for your contribution.